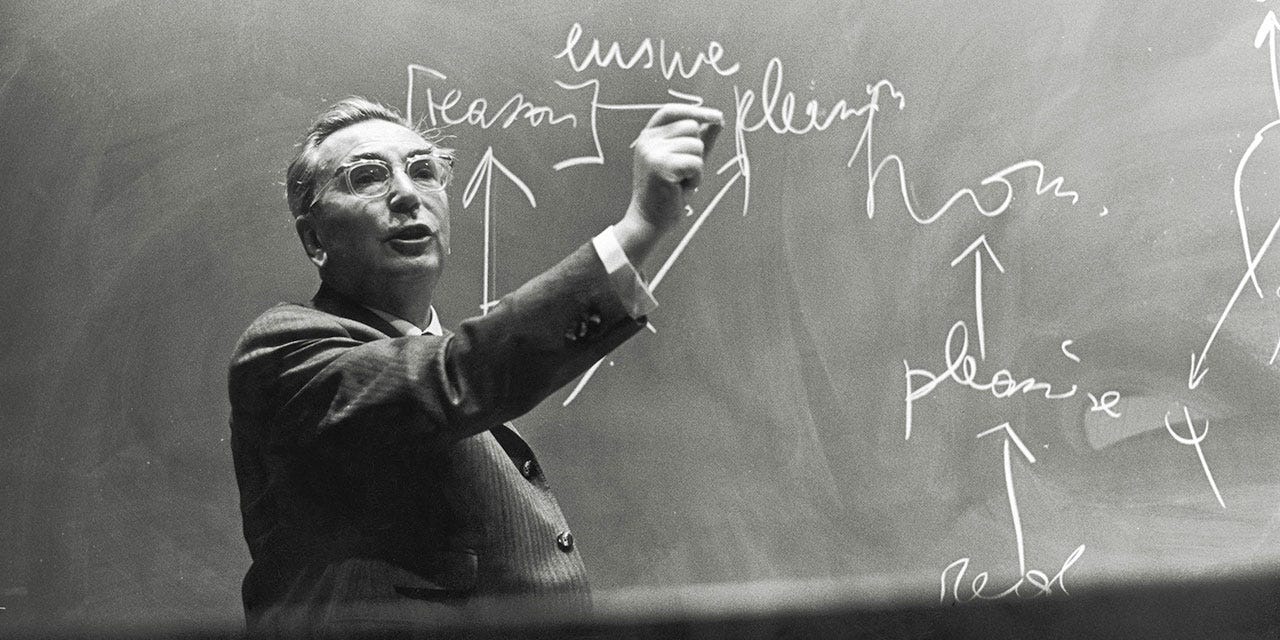

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

book review

Man’s Search for Meaning, first published in 1946, is an autobiographical book by psychologist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl. This seminal book, which quickly became a bestseller, recounts the horrors Frankl experienced in four different Nazi concentration camps and explores his method of finding meaning in all forms of existence. He wrote this book in nine days just weeks after he was liberated from the concentration camps.

Frankl separates the book into two parts. The first part deals with his personal experiences during the Holocaust and how he survived the concentration camps. The second part deals with his idea of logotherapy, a school of psychotherapy that he founded. Logotherapy is the idea that searching for a meaning in life is the primary motivational force of an individual.

While I have heard great things about this book for years, I didn’t find it as impactful as I expected. While I generally agree with Frankl’s main idea that the search for meaning is incredibly important for life, the book felt oddly simplistic and brief in recounting his life in the concentration camps.

Frankl repeatedly talks about how everyone had grown so incredibly numb to all forms of human suffering after assimilating themselves into the camps which could explain why the book lacks emotions and deals with the countless unjust deaths in a somewhat detached manner.

Some of the more interesting ideas are that of the decent and indecent man, life having meaning continuously even in the worst of human suffering, having love as the ultimate goal, importance of hope in staying alive but not too much hope that one believes in delusions.

Frankl continuously talks about how having a meaning can lead to people surviving. He says that this meaning gives people hope that makes them survive even the worst conditions known to man. He also says that once a person loses meaning, they start to slowly die and eventually succumb to illness or fail in the face of pressure and die.

Frankl personally talks about how he had a manuscript for his life’s work up till that point that he hid in his coat when he was first transported to the concentration camp. Like the rest of his belongings, he had to leave everything behind before entering the camp else he would face death. He talks about how during his illness in camp or when he had time, he would try to recreate the manuscript from memory on small scrap pieces of paper or its equivalent. He said that this gave him the greatest meaning and helped him to survive.

He also talks about thinking of his wife and how his love for her brought meaning.

That brought thoughts of my own wife to mind. And as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on icy spots, supporting each other time and again, dragging one another up and onward, nothing was said, but we both knew: each of us was thinking of his wife. Occasionally I looked at the sky, where the stars were fading and the pink light of the morning was beginning to spread behind a dark bank of clouds. But my mind clung to my wife's image, imagining it with an uncanny acuteness. I heard her answering me, saw her smile, her frank and encouraging look. Real or not, her look was then more luminous than the sun which was beginning to rise. A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love. I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way—an honorable way— in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, "The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory." In front of me a man stumbled and those following him fell on top of him. The guard rushed over and used his whip on them all. Thus my thoughts were interrupted for a few minutes. But soon my soul found its way back from the prisoner's existence to another world, and I resumed talk with my loved one: I asked her questions, and she answered; she questioned me in return, and I answered... My mind still clung to the image of my wife. A thought crossed my mind: I didn't even know if she were still alive. I knew only one thing—which I have learned well by now: Love goes very far beyond the physical person of the beloved. It finds its deepest meaning in his spiritual being, his inner self. Whether or not he is actually present, whether or not he is still alive at all, ceases somehow to be of importance. I did not know whether my wife was alive, and I had no means of finding out (during all my prison life there was no outgoing or incoming mail); but at that moment it ceased to matter. There was no need for me to know; nothing could touch the strength of my love, my thoughts, and the image of my beloved. Had I known then that my wife was dead, I think that I would still have given myself, undisturbed by that knowledge, to the contemplation of her image, and that my mental conversation with her would have been just as vivid and just as satisfying. "Set me like a seal upon thy heart, love is as strong as death."

Another story from the book that was profound was the story of someone who had a dream about the exact day of his liberation. When he wasn’t freed on that day, he lost all hope and here’s what happened.

I once had a dramatic demonstration of the close link between the loss of faith in the future and this dangerous giving up. F, my senior block warden, a fairly well-known composer and librettist, confided in me one day: 'I would like to tell you something, Doctor. I have had a strange dream. A voice told me that I could wish for something, that I should only say what I wanted to know, and all my questions would be answered. What do you think I asked? That I would like to know when the war would be over for me. You know what I mean, Doctor - for me! I wanted to know when we, when our camp, would be liberated and our sufferings come to an end.'

'And when did you have this dream?' I asked.

'In February, 1945,' he answered. It was then the beginning of March.

'What did your dream voice answer?"

Furtively he whispered to me, "March thirtieth."

When F told me about his dream, he was still full of hope and convinced that the voice of his dream would be right. But as the promised day drew nearer, the war news which reached our camp made it appear very unlikely that we would be free on the promised date. On March twenty-ninth, F suddenly became ill and ran a high temperature. On March thirtieth, the day his prophecy had told him that the war and suffering would be over for him, he became delirious and lost consciousness. On March thirty-first, he was dead. To all outward appearances, he had died of typhus.

Those who know how close the connection is between the state of mind of a man—his courage and hope, or lack of them—and the state of immunity of his body will understand that the sudden loss of hope and courage can have a deadly effect. The ultimate cause of my friend's death was that the expected liberation did not come and he was severely disappointed. This suddenly lowered his body's resistance against the latent typhus infection. His faith in the future and his will to live had become paralyzed and his body fell victim to illness—and thus the voice of his dream was right after all.

The observations of this one case and the conclusion drawn from them are in accordance with something that was drawn to my attention by the chief doctor of our concentration camp. The death rate in the week between Christmas, 1944, and New Year's, 1945, increased in camp beyond all previous experience. In his opinion, the explanation for this increase did not lie in the harder working conditions or the deterioration of our food supplies or a change of weather or new epidemics. It was simply that the majority of the prisoners had lived in the naive hope that they would be home again by Christmas. As the time drew near and there was no encouraging news, the prisoners lost courage and disappointment overcame them. This had a dangerous influence on their powers of resistance and a great number of them died.

As we said before, any attempt to restore a man's inner strength in the camp had first to succeed in showing him some future goal. Nietzsche's words, "He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how," could be the guiding motto for all psychotherapeutic and psychohygienic efforts regarding prisoners

Moreover, while I felt the first part was interesting and useful to think about various ideas that he dealt with, the second part feels more like an advertisement for his theory of logotherapy especially when he talked about helping his clients in their normal day to day lives.

The contrast between his lived experience experiencing one of the greatest horrors in Nazi concentration camps and the struggles of normal working day people was stark and jarring. I think this was an updated edition which would explain things but still the juxtaposition of these two parts in the same book remains bizarre.

Overall, I would recommend reading the first half of this book for Frankl's experiences in the concentration camps and how hope can help one survive even in the darkest of times. The second part focusing on logotherapy, might only be of interest to those studying psychology.

While I didn’t find Man’s Search for Meaning as impactful as its reputation had led me to expect, I think that its ideas are still deeply profound and insightful. Maybe I will glean more from this book if revisit it in the future with more life experience.